The Japanese Missions to Tang China, 7th-9th Centuries

The Japanese Missions to Tang China, 7th-9th Centuries

On nineteen occasions from 630 to 894, the Japanese court appointed official envoys to Tang China known as kentōshi to serve as political and cultural representatives to China. Fourteen of these missions completed the arduous journey to and from the Chinese capital. The missions brought back elements of Tang civilization that profoundly affected Japan’s government, economics, culture, and religion. The kentōshi missions were large, numbering up to six hundred individuals, and among their members were students and monks who restructured Japan’s ancient state and inspired such watershed events in early Japanese institutional history as the Taika Reform (645), which applied Tang land reform to Japanese agricultural lands to empower the court, and the Taihō Code (701), which systematized under the Japanese emperor a Chinese-style bureaucratic structure. The members of these embassies to China were also involved in the exchange of goods—official tributary items and, most probably, goods traded privately by individual mission members. They transported raw materials such as amber, agate, and a variety of silk textiles, and exchanged them for Chinese goods, such as books, musical instruments, religious writings, and Buddhist images.INTRODUCTION

Selective borrowings of continental culture were critical to the development of early Japanese society. Immigration and regional trade with the southern Korean peninsula accounted for much of the spread of continental culture in Japan, but the Japanese also established and maintained contact with the continent by sending and receiving official embassies. Diplomatic trade missions to China date to as early as the first centuries C.E., when the small Japanese states of Nu and Yamatai sent embassies (respectively) to the Later Han and Wei courts in China. After the fall of the Later Han dynasty in 220 C.E., China remained largely divided into regional kingdoms until the end of the 6th century. The resulting political instability in China left the newly evolving Yamato court without a clear long-term Chinese partner with which to establish diplomatic exchange. The Japanese did send embassies to China during this time, but exchanges of embassies with the Korean kingdoms of Paekche and Silla were more critical for informing the Japanese of cultural developments on the continent. One such embassy from Paekche came to Japan in 552 (or 538 depending on the primary source) bearing an image of the Buddha, copies of Buddhist sutras, and a Buddhist monk. This official court exchange marked the first recorded introduction of Buddhism to the Japanese elite. The subsequent study of Buddhism in Japan fostered greater dissemination of Chinese language literacy along with Chinese ideas of governance, philosophy, and social harmony, all of which are inherent in the written Chinese script.

ENVOYS TO SUI CHINA: 600-614

+ to enlarge

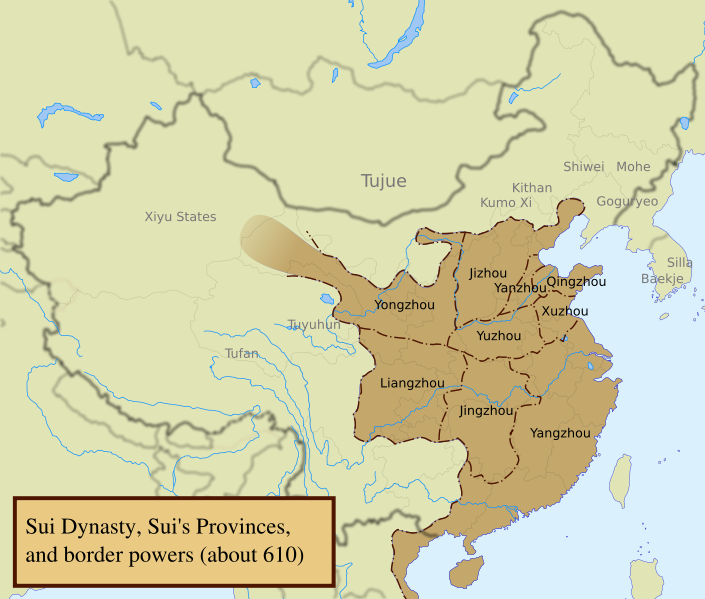

+ to enlargeCambridge History of China, vol.3, map about Sui dynasty's divisions. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike 3.0 License. In short: you are free to share and make derivative works of the file under the conditions that you appropriately attribute it, and that you distribute it only under a license identical to this one. (Ed. Note: Baekje in this map is referred to as Paekche in this essay).

KENTŌSHI (ENVOYS TO TANG CHINA): 630-838

The first mission to Tang authorized by the Japanese court departed in 630. Over the next two hundred years, fifteen kentōshi missions voyaged to and from the mainland (all reached the Tang capital with the exception of the 667 mission, which ventured only as far as Paekche), making possible the assimilation of Tang culture and civilization. By the time the last kentōshi ship returned from China in 840, the Japanese had been able to institute a centralized Chinese-style bureaucracy, penal and administrative codes, Chinese standardized measurements for rice land assessment, and population registers. The Japanese also adopted the Chinese calendar and ideas of Chinese geomancy, made evident in the construction of Heijō (Nara) in 710 and Heian-kyo (Kyoto) in 794, each of which were modeled on the Tang capital city of Chang-an.

The kentōshi missions carried students and scholars of Tang civilization to and from China, some of whom remained on the continent 30 years or more before returning to disseminate the knowledge they learned. Saichō (767-822) and Kūkai (774-835) serve as prominent examples of religious scholars who sailed as part of the 804 embassy to China. Upon their return to Japan, the former founded the Tendai sect of Buddhism, and the latter founded the Shingon sect and went on to become one of Japan’s most distinguished scholars. The importance of these two individuals to the development of Japan cannot be understated. Each man voyaged to China as part of an official embassy in order to familiarize himself with little understood Buddhist sects. Each returned to establish his new sect in Japan. Had Saichō and Kūkai not sailed as a part of the 804 embassy, the Japan of today would be quite different. Saichō’s Tendai sect eventually inspired the development of new Japanese sub-sects that made Buddhism popular among the common people of Japan, while Kūkai’s Shingon sect profoundly influenced the thought and aesthetics of the Heian court aristocracy.

Above all else, the success of the Tang missions is demonstrated by the great volume of knowledge they transmitted to Japan. By the end of the 9th century, the Japanese possessed at least 1700 Chinese texts including Confucian treatises on government and social harmony, as well as works of history, poetry, divination, and medicine. It is important to keep in mind, however, that the Japanese did not borrow Chinese institutions or practices indiscriminately; rather, they attempted to assimilate what they found useful into their own society.

“I WAS FORTUNATE INDEED!” A FIRST PERSON ACCOUNT OF THE MISSION OF 777 C.E.

The mission was comprised of four vessels that departed on 6:24 (lunar month / day) from western Japan. As many as 600 people may have sailed with this embassy as each ship could accommodate up to 150 people. The mission’s voyage to the mainland was uneventful. In just under 10 days the ships arrived safely at Yangzhou, China, having traversed a distance of approximately 925 kilometers (575 miles). However, as these ships returned to Japan nearly a year and a half later, fatal mishaps occurred. Disaster struck shortly after the ships embarked from Suzhou China to return to Japan in the eleventh and twelfth lunar months of 778.

Below are excerpts from a first person account by the Councilor to the Envoy, Ōtomo no Sukune, regarding the 777 mission’s voyages to and from the continent. His passage to China was uneventful; however, his account of his return to Japan on Ship No.1 demonstrates vividly the dangers he and others faced at sea.

Last year (777 C.E.) on 6:24, our four vessels set sail across the seas bound for China. On 7:3, we reached Hailingxian Sub-prefecture in Yangzhou and dropped anchor. On 8:29, we arrived at the Yangzhou regional office. We petitioned the regional governor, Chen Shaoyou, and were granted permission for 65 of our number to enter the capital. On 10:16, we set out for the capital. [Omitted]

We arrived at Chang’an on the thirteenth day of the first month. We had an audience with the Tang Emperor on 3:24 (of 778 C.E.). [Omitted]

On 6:25 we reached Weiyang (Yanzhou) [to prepare for the voyage back to Japan]. On 9:3, we set sail from the mouth of the Yangzi. We stopped at Changdan Sub-prefecture in Suzhou to await the winds. [Omitted]

On 11:5, with favorable winds behind us, Ship No. 1 and Ship No. 2 set sail together on the voyage home. While in the midst of the sea on the eighth day (of the month) at approximately 8 PM, the winds began to blow violently and the ocean waves became large. The sides and planks of the ship were torn and the vessel filled with sea water. The deck came apart and washed away. People and supplies floated about in the sea, and neither food nor drinking water was saved. The Vice-envoy, Ono no Ason no Iwane, together with 38 (Japanese), drowned at the same time as Zhao Baoying (an envoy from Tang accompanying the Japanese home to Japan) and 25 (Chinese). I alone managed to make my way to the railing at the back corner of the stern where I surveyed my surroundings and awaited the end.

At approximately 4 AM on the 11th day of the month, the mast fell to the bottom of the ship. The vessel then broke into two sections and drifted separately toward parts unknown. More than 40 people piled upon a part of the stern measuring only about three meters on all four sides as they clung for dear life. After a mooring line was cut and the rudder lost, this part of the vessel floated a little higher in the water.

The survivors shed their clothing and sat upon the top of the broken vessel in the nude. The survivors experienced six days without food or water, and then on the 13th, at approximately 10 PM, the broken part of the vessel drifted ashore at Nishinonakashima in Amakusa in the province of Hinomichinoshiri (Higo).

By the mercy of Heaven, I was granted a second chance at life. I was fortunate indeed!

(Translated by author from an 8th century Shoku Nihongi account.)

After the initial destruction of Ship No. 1 by the storm, the seas calmed and the parts of the ship that had broken apart drifted to the northeast along the ocean current. Both parts of the vessel, as well as Ship No. 2, arrived on the shores of Kyushu, Japan on the same day. Ship No. 3 and Ship No. 4 also ran into mishap. Ship No. 3 ran into opposing winds three days out of China. It returned to China for repairs, but safely landed in Japan on the 20th day of the 11th month. Ship No. 4 landed on Cheju Island (Korea), where crew members were captured by islanders. Eventually 40 escaped and sailed to Japan, arriving on the 7th day of the 12th lunar month of 778.

END OF THE MISSIONS TO TANG

At about the time that the kentōshi missions came to a close, the Tang dynasty was in decline. The last official mission was sent to China in 838. There was another mission planned for 894, but the Court cancelled it after protestation from the ambassador, Sugawara no Michizane. It is supposed that the missions ceased because conditions had become too unstable in Tang and because Japan no longer found it necessary to import aspects of Tang culture or conduct diplomacy with its neighbors. The emergence of an East Asian trade network may have played a part as well. As the kentōshi missions were being deemed unnecessary, private merchants were coming to Japan in increasingly greater numbers and bringing many of the goods the court elite had obtained through these missions. The newly burgeoning merchant exchange may have rendered the trading activities of the Tang embassies unnecessary.

Further readings:

There is a plethora of Japanese language research regarding the missions to Tang. In English, Edwin Reischauer’s 1955 translation, Ennin’s Diary: the Record of a Pilgrimage to China in Search of the Law and his book of the same year, Ennin’s Travels in Tang China, are by far the best known works regarding the subject of the Japanese missions to Tang China. Reischauer’s books introduced English language scholars to an exciting chapter in Japanese and Chinese history. Robert Borgen’s “The Japanese Mission to China, 801-806,” published in Monumenta Nipponica in 1982, likewise did much to advance western language scholarship. Both Reischauer and Borgen dealt specifically with two ninth-century missions. The first comprehensive study of more than one kentōshi mission came in Charlotte von Verschuer’s Les Relations Officielles Du Japon Avec La Chine, a groundbreaking study that was published in French in 1985. This work focuses primarily on the official diplomatic exchange between Japan and Tang China and includes discussion of those kentōshi missions that were dispatched during the eighth and ninth centuries. Von Verschuer has since followed up her initial work with studies published in both English and French regarding commercial and diplomatic exchange between Japan and its neighbors during the Ancient and Medieval periods. Another influential work that introduced English readers to certain aspects of the kentōshi official exchange was Wang Zhen-Ping’s “Sino-Japanese Relations before the Eleventh Century: Modes of Diplomatic Communication Reexamined in Terms of the Concept of Reciprocity,” which was published in 1989 as a dissertation for Princeton University.

Douglas Fuqua is Vice Chancellor and Associate Professor at Hawaii Tokai International College. His areas of research include early interactions between Japan and China.