The Evolution of the Tea Ceremony

The Evolution of the Tea Ceremony

According to the records, tea was first introduced to Japan from China in the early ninth century by Japanese Buddhist monks. This was during the age, which extended from the late sixth until the mid-ninth centuries, when Japan borrowed extensively from both China and Korea in forming its first centralized state, a state headed by the emperor and his court, which from 794 was situated in Kyoto (known also as Heian). Tea was esteemed in China both for its medicinal value (it contains tannic acid, which is good for one’s health) and as an elegant drink. The Japanese emperor’s court also extolled tea’s elegance, praising in poetry its purported “spiritual” qualities; and monks in Buddhist temples made special use of tea, which is a stimulant, to prevent drowsiness during meditation.

When the Japanese court in the mid-ninth century sent the last of the missions to China that were the means for its extensive cultural borrowing from the continent, tea drinking seems essentially to have died out in Japan. After a lapse of some three hundred years, however, tea was reintroduced from China in the late twelfth century by a priest of the Zen sect of Buddhism, and over the next few centuries tea-drinking spread among all classes of Japanese society.

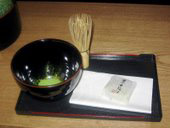

Sometime during the tenth century the Chinese had begun to use powdered tea (the tea leaves are steamed, dried, and then crushed into powder) and developed the split bamboo whisk to stir it into hot water. Later, the Chinese abandoned powdered tea, and today virtually all tea drinkers in the world, including the Japanese in their daily lives, prepare tea by means of infusion (dipping or placing the leaves in hot water), whether they drink black (fermented) tea, oolong (partially fermented) tea, or green (unfermented) tea. Powdered tea is used only in the Japanese tea ceremony (chanoyu), which was created in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries in the midst of Japan’s samurai-dominated medieval age (1185-1568). It is green powdered tea, which is scooped into a rather large bowl and whipped into a frothy, bitter-tasting drink with hot water poured from a kettle.

+ enlarge image

There are four major aspects of chanoyu:

1. Rules. Rules for the preparation, serving, and consumption of tea were developed into a “ceremony” that was clearly distinguishable from the mundane, everyday act of tea drinking. The rules originally came from the monastic rules that governed the lives of priests and monks of Zen Buddhism, which, like Zen itself, were imported from China. Over time, the various schools of chanoyu that were established in Japan developed their own particular rules. But one rule that became common to all the schools—and indeed to chanoyu itself—was the movement of the entire process of preparing, serving, and consuming tea into one room—the tea room. In chanoyu the host brings everything necessary for tea preparation into the tea room, where he prepares tea and serves his guests and also provides them with a simple meal (the tea is drunk separately from the meal). The host himself/herself does not partake of either the tea or the meal.

2. Setting. The tea room evolved as a variant of a type of room known as shoin (library or den) that was modeled on a room in Zen temples that priests and monks used during their leisure time. The shoin-style room became what we know today as the prototypical Japanese room. Its main features include: matting (tatami) covering the entire floor; two types of sliding doors, one a latticed door covered with translucent rice paper and the other a framed, cardboard door; and three installed features—an alcove, asymmetrical shelves, and a floor-level desk. The tea room, as a variant of the standard shoin room, often does not have all three of the last-mentioned features. Many tea rooms, for example, have only an alcove. During a tea ceremony, the alcove usually contains a scroll of calligraphy, a flower arrangement, or both. Some tea rooms have another, unique feature: a “crawling-in” entranceway. This is a space, perhaps three feet square, cut at floor level into one of the walls. Using this entranceway obliges one to crawl on hands and knees into the tea room. It is an act of personal humility symbolizing the shedding of social distinctions and ranks for the duration of the tea ceremony.

3. Behavior. Two of the qualities of human behavior especially treasured in chanoyu are harmony and respect. The host and his/her guests seek to establish and maintain an atmosphere of perfect harmony during a tea ceremony; such harmony is reinforced by mutual respect among the host and guests. Chanoyu was the product of the most protracted period of disorder in Japanese history—the late fifteenth century and most of the sixteenth century, a time known as the age of “war in the provinces.” We can speculate that chanoyu was developed to provide at least a brief escape from the incessant fighting among the samurai of that age. People yearn for order in times of disorder. Governed by the spirit of harmony and respect, order was temporarily restored for those who entered the microscopic world of the tea room to partake of chanoyu.

4. Taste. Chanoyu strives for aesthetic perfection. Through the ages tea masters have designed tea rooms with the utmost care to reflect their architectural tastes. They have selected the articles for chanoyu, including ceramic bowls and water containers, lacquered tea caddies, bamboo whisks and scoops, and iron kettles, in accordance with the aesthetic values most treasured by the tea world and with their own personal preferences. For display in the alcove, they have chosen scrolls of calligraphy appropriate to the time and season of each of their tea gatherings.

There are two kinds of tea ceremony, formal and informal. Surprisingly, perhaps, it is the informal kind, known as wabicha, or tea (cha) based on the wabi aesthetic, that is the more highly esteemed. In formal chanoyu, the utensils for tea are placed upon and then taken from a two-tiered lacquer stand called daisu. In wabicha, the daisu is dispensed with and the utensils are placed directly on the mat used by the host. The term wabi defies precise definition, but one scholar has sought to describe it as comprising three kinds of beauty: a simple, unpretentious beauty; an imperfect, irregular beauty; and an austere, stark beauty. To tea connoisseurs these beauties—wabi—are embodied probably most fully in the ceramic ware of chanoyu; for example, in a simple clay bowl only partially glazed and of muted color that has a rough texture and is perhaps slightly misshapen.

The standard size tea room for wabicha is four and a half mats or nine feet square. But the greatest of the tea masters, Sen no Rikyū (Rikyū of the Sen family), who lived during the late sixteenth century, designed a tea room of two mats or six feet square (the standard mat is six feet by three feet). This tea room was named Taian and still exists (in the suburbs of Kyoto). In its nearly miniscule size and simple, stark construction and in its absence of virtually all ornamentation, Taian has been called the “North Pole” of Japanese aesthetics and is considered the epitome of wabi taste.

In pre-modern times—that is, before the Meiji Restoration of 1868 that ushered Japan into the modern world—chanoyu was almost exclusively a male art. But in the early years of the modern period (the late nineteenth century) it was introduced into the public school curricula as a means for instructing young ladies in proper decorum and etiquette. Today, chanoyu is largely female.

Chanoyu is a unique Japanese art. There is nothing else like it in the world. The early twentieth-century art critic Okakura Kakuzō described it as “. . . a cult founded on the adoration of the beautiful among the sordid facts of everyday existence. It inculcates purity and harmony, the mystery of mutual charity, the romanticism of the social order. It is essentially a worship of the imperfect . . .” Yet Okakura apparently believed that non-Japanese—at least Westerners—were unlikely to appreciate chanoyu, as we can see in the following rather bitter words: “The average Westerner, in his sleek complacency, will see in the tea ceremony but another instance of the thousand and one oddities which constitute the quaintness and childishness of the East to him.” In fact, Westerners and other non-Japanese in recent years have shown a considerable interest in and appreciation of chanoyu. The leading tea schools have branches in countries throughout the world and, although the number of non-Japanese who seriously practice chanoyu may not be great, appreciation of its arts, including room construction, ceramic ware, lacquer ware, flower arranging, and calligraphy, are widely admired and have been the subjects of countless exhibitions throughout the world. Chanoyu, with a history of more than five hundred years, remains today alive and rather well both inside and outside Japan.