Learning from Babysan

Learning from Babysan

The Japanese government formally agreed to surrender to the Allied nations of World War II on August 14, 1945. Famously, at noon on the following day Emperor Hirohito’s taped announcement of surrender was broadcast to the nation by radio. Less than two weeks later, the first United States troops started to land at airfields and ports on the main island of Honshu, to begin the Allied Occupation of Japan (1945-1952). By the end of 1945, nearly half a million American soldiers were stationed throughout the country. They were joined in 1946 by another 40,000-plus troops from the British Commonwealth Forces—Britons, Australians, Indians, and New Zealanders.

The numbers of Allied soldiers in Japan fell sharply over 1946 and 1947, as it became clear that the Occupation would be largely unopposed, and peaceful. Still, during its seven years there were never fewer than 100,000 military personnel—mostly men between the ages of 18 and 24—garrisoned in dozens of bases scattered about the four main islands of Japan. During the Korean War (1951-1953), American troop strength in Japan actually rose again, reaching the figure of 260,000 GIs by 1952.[1] Nor did those soldiers necessarily go home when Japan regained its sovereignty in that year. The negotiations that ended the Occupation included a bilateral security treaty between Japan and the U.S. that provided for the indefinite continued existence of U.S. military bases. Today, there are still some 85 U.S. military installations in Japan. Most are in Okinawa, the group of islands that the U.S. military controlled until their reversion to Japan in 1972, but there continue to exist on the main islands a number of important bases belonging to the U.S. Marine Corps (Iwakuni, Camp Fuji), Air Force (Yokota, Misawa), Navy (Sasebo, Yokosuka, Atsugi), and Army (Zama).[2]

The constant cycling of hundreds of thousands of mostly American soldiers in and out of Japan had enormous effects on both countries, and on the world, that are still reverberating to this day. While scholars have studied many aspects of the Occupation, until recently the tendency has been to focus primarily on the one-way and top-down story of how Allied (primarily U.S.) policies and interests affected Japan, and especially Japanese elites: politicians, policymakers, business leaders, and intellectuals. Newer research has explored the active role of Japanese themselves in shaping the Occupation, and also some of the more quotidian aspects of the Occupation experience for ordinary as well as elite Japanese. A result of the latter project, in particular, has been fresh recognition of the impact of Allied soldiers and their bases on everyday life in Japan. What still tends to be overlooked, however, is the equally profound impact of Japan on its occupiers. The youthful Americans, Australians, and other Allied soldiers who completed tours of duty in Japan were also shaped by their experiences, which they took home with them when they departed—or on to other stops in their military careers.

One readily accessible body of materials directly pertaining to the experience of American GIs, especially, is to be found in American popular culture. This essay examines a single example: a collection of cartoons drawn and written by a Navy serviceman in the final two years of the Occupation, and republished in Japan and the U.S. in 1953 as a book titled Babysan: A Private Look at the Japanese Occupation.[3] In the following sections I offer some suggestions as to how Babysan might be read as a means of gaining insight into the Occupation for the occupiers as well as the occupied, in Japan, the U.S., and beyond.

I. What Babysan Tells Us

Bill Hume (1916-2009), the main author of Babysan, was a naval reservist from Missouri who was called up in 1951 to serve in Japan at Atsugi naval air base. A commercial artist in civilian life, Hume began publishing cartoons about American soldiers in various military periodicals, such as the Pacific editions of the Stars and Stripes and Navy Times. His best-known cartoons concerned the erotic interactions of Navy servicemen with young Japanese women or, as he dubbed them, “Babysan.” Hume and his co-author, a Navy journalist named John Annarino (1930-2009), explain in Babysan that the name is an American-Japanese blend:

San may be assumed to mean mister, missus, master or miss. Babysan, then, can be translated literally to mean “Miss Baby.” The American, seeing a strange girl on the street, can’t just yell, “hey, baby!” He is in Japan, where politeness is a necessity and not a luxury, so he deftly adds the title of respect. It speeds up introductions. [Babysan, 16]

Most directly, Babysan offers us insights into the critical question of how American soldiers actually behaved toward Japanese civilians: What was the nature of relations between occupiers and occupied? In addition to explaining the origins of the term “Babysan,” for example, the quotation above paints a vivid picture of what must have been a common scene on Occupation-era streets. Nor did Allied soldiers merely shout greetings at Japanese women. In recent years, a number of studies have explored the ubiquity during the occupation of Japan, as in the occupations of other countries after World War II, of sexual relations between occupying troops and civilian natives—or what the military called, disapprovingly, “fraternization.” As many as 70,000 women worked as prostitutes in brothels and other facilities that were established by the Japanese government to entertain (and pacify) Allied soldiers during the early years of the Occupation. And tens of thousands of other Japanese exchanged sexual favors for money or goods on a more casual, private basis in and around military installations. Yet the type of woman depicted in Babysan was not exactly an ordinary sex worker—or panpan, as they were often called—who made a living from short-term sexual encounters with servicemen. Hume focused, rather, on the greyer category of what were sometimes referred to as onrii (from “only” or “only one”), or women who engaged in serial, ostensibly monogamous relationships with “only one” uniformed lover at a time, and who received various forms of material compensation in return.[4]

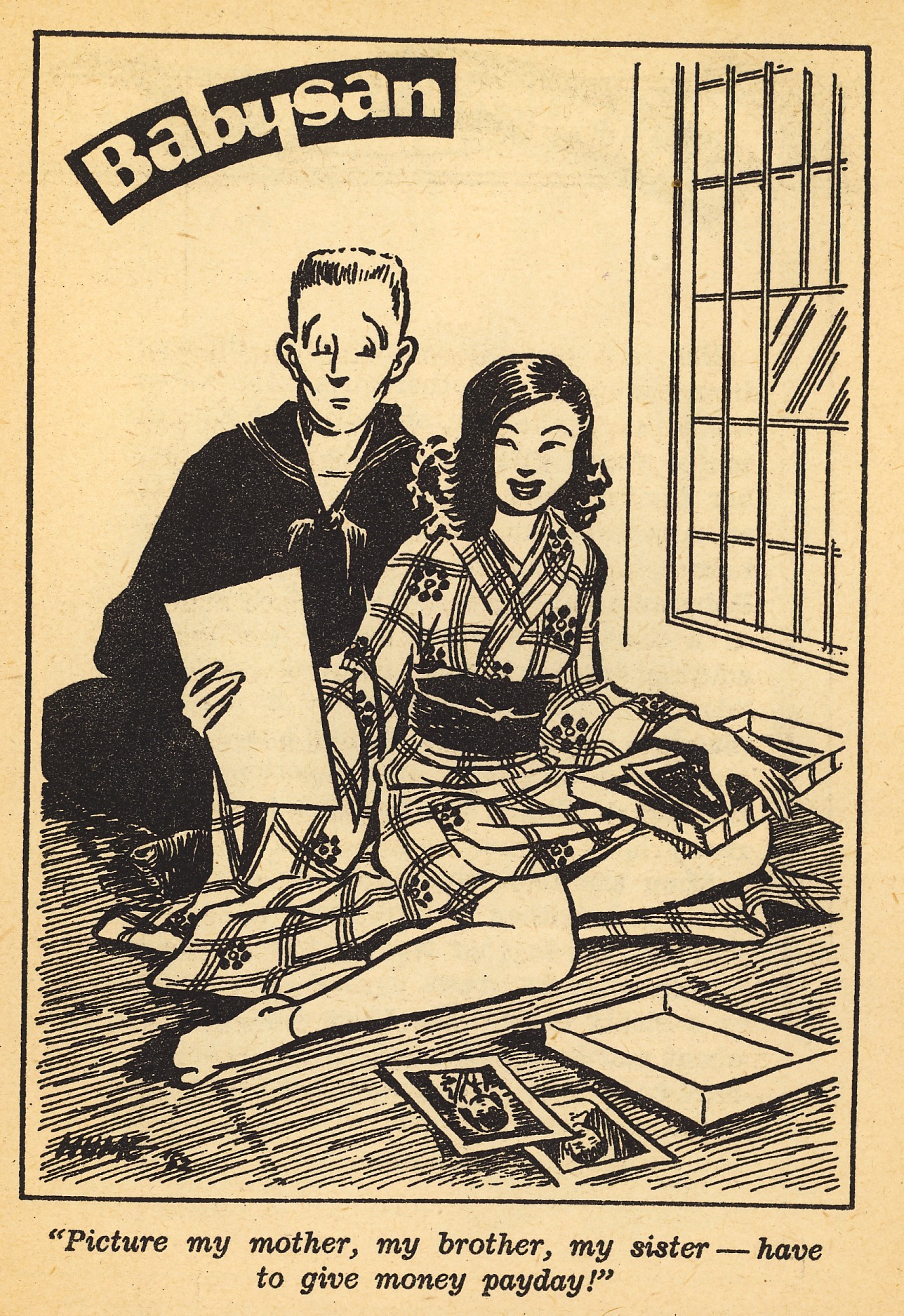

As a document produced by and for American servicemen, Babysan may reveal more about them than it does about the women it purports to describe—but there are genuine if sometimes oblique insights here into the latter and their world. For example, much of the humor in Babysan derives from the tension between the American sailor’s good-willed, often naïve expectations of his new girlfriend (fidelity, romantic attachment, regular sexual availability) and the Japanese woman’s pragmatic and even deceitful determination to extract as much from him (and other Americans) as possible. Several cartoons note that she claims she has a family to support, and that her lover’s gifts are necessary for their survival, as well as her own. [figure 1]

Fig. 1

Her past possibly is not much different from that of many other girls. Her father was killed in the war, and although she was just a young girl she had to work to help her family. . . . Her aged mother is bent from toil in rice paddies; her brother wants to be a baseball player when he grows up, but of course he is a sickly child. The tales Babysan tells about members of her family are sometimes hard to believe. It seems uncanny that their body temperatures should rise and fall with Babysan’s financial status. [Babysan, 96]

The writer expresses skepticism, but many young women in Japan, as in war-devastated countries around the world, did indeed find themselves in such straits, and the access some were able to gain to the goods and cash brought by Allied personnel helped to support extended networks of family and others during a time of great material scarcity.

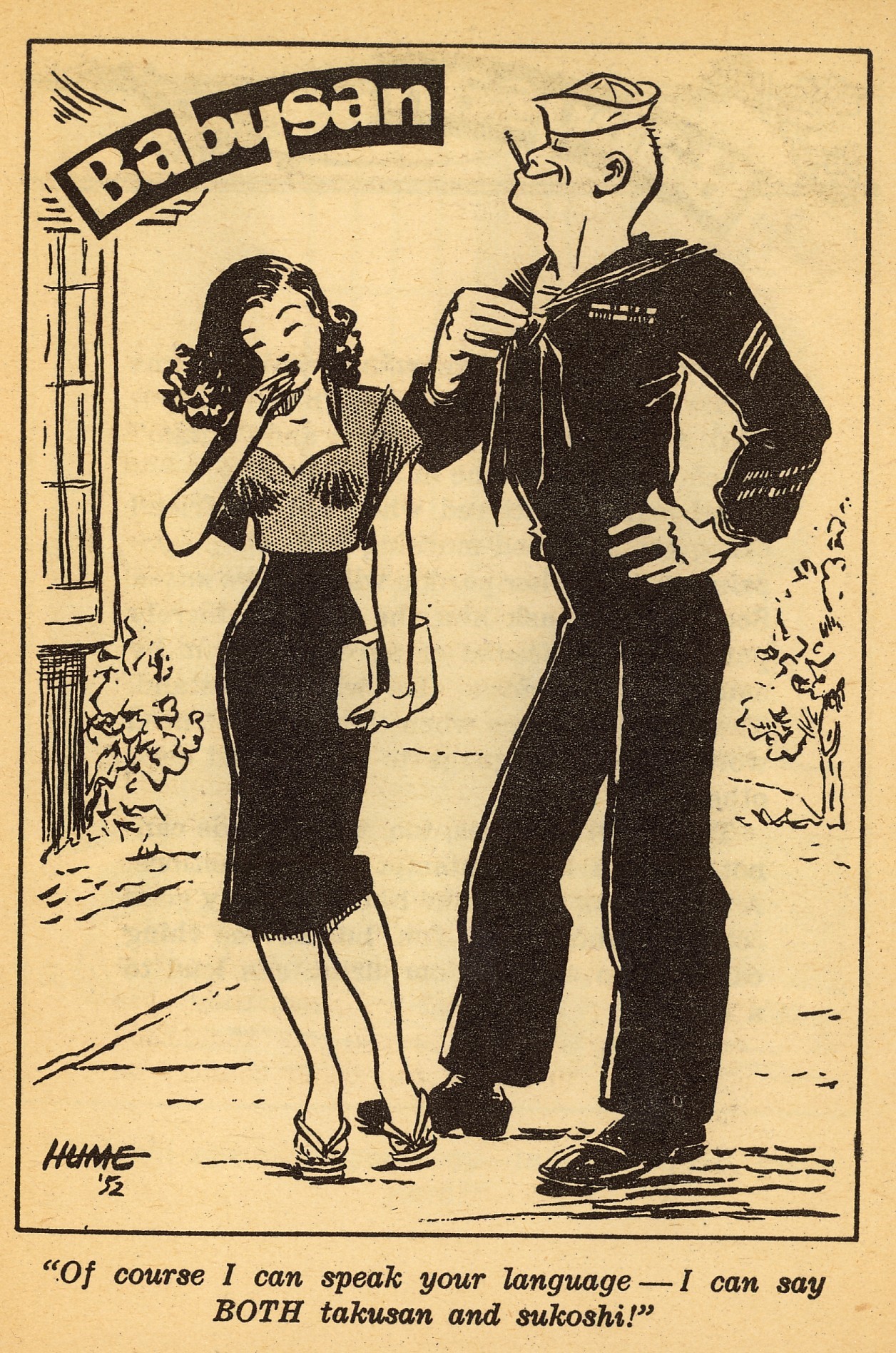

Also credible are the glimpses Babysan reveals of the hybrid mixtures of American and Japanese culture that sprang up almost immediately in the spaces of contact between servicemen and native women. The very term Babysan, along with many other examples of “Panglish” that appear in the cartoons (and in a mock-helpful glossary at the end of Babysan), attest to the linguistic creativity unleashed by military occupation. As suggested by several cartoons, as well as the book’s glossary, the ability of Japanese women to communicate in English was facilitated by the way in which certain Japanese terms and phrases became familiar to servicemen [Babysan, 89, 124-127]. The resulting pidgin was not an equal mix—inevitably the power imbalance favored English—but the phenomenon hints at the possibility that the impact of the Occupation included some degree of Japanization, and not simply one-way Americanization or Westernization. [figure 2]

Fig. 2

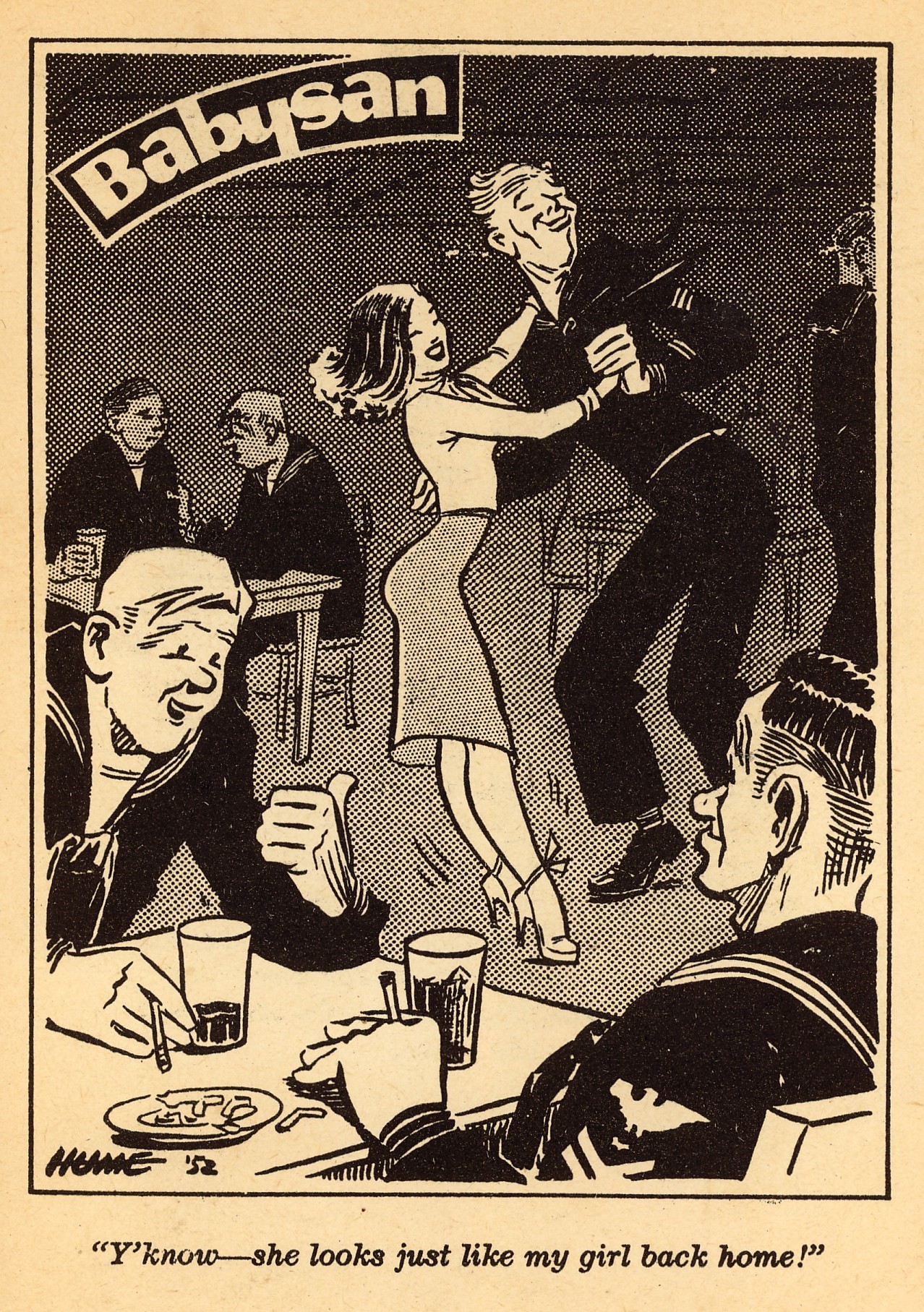

Similarly, there are several references to another hybrid cultural form that flourished in the zone of contact between occupiers and occupied: popular music. One cartoon depicts Babysan as she “jives and jitterbugs her way across the clubroom floor” with a sailor. [figure 3]

Fig. 3

The accompanying text identifies the tune as “Japanese Rhumba” [Babysan, 10-11]. “Japanese Rumba,” released in 1951 on the Japanese label Nippon Columbia, was just one of numerous hits—such as “Tokyo Boogie Woogie” (1949) or “Gomen-nasai (Forgive Me)” (1953)—that were produced in occupied (or recently occupied) Japan, and circulated there and beyond, in other parts of the world.[5]

II. What Babysan Doesn’t Tell Us

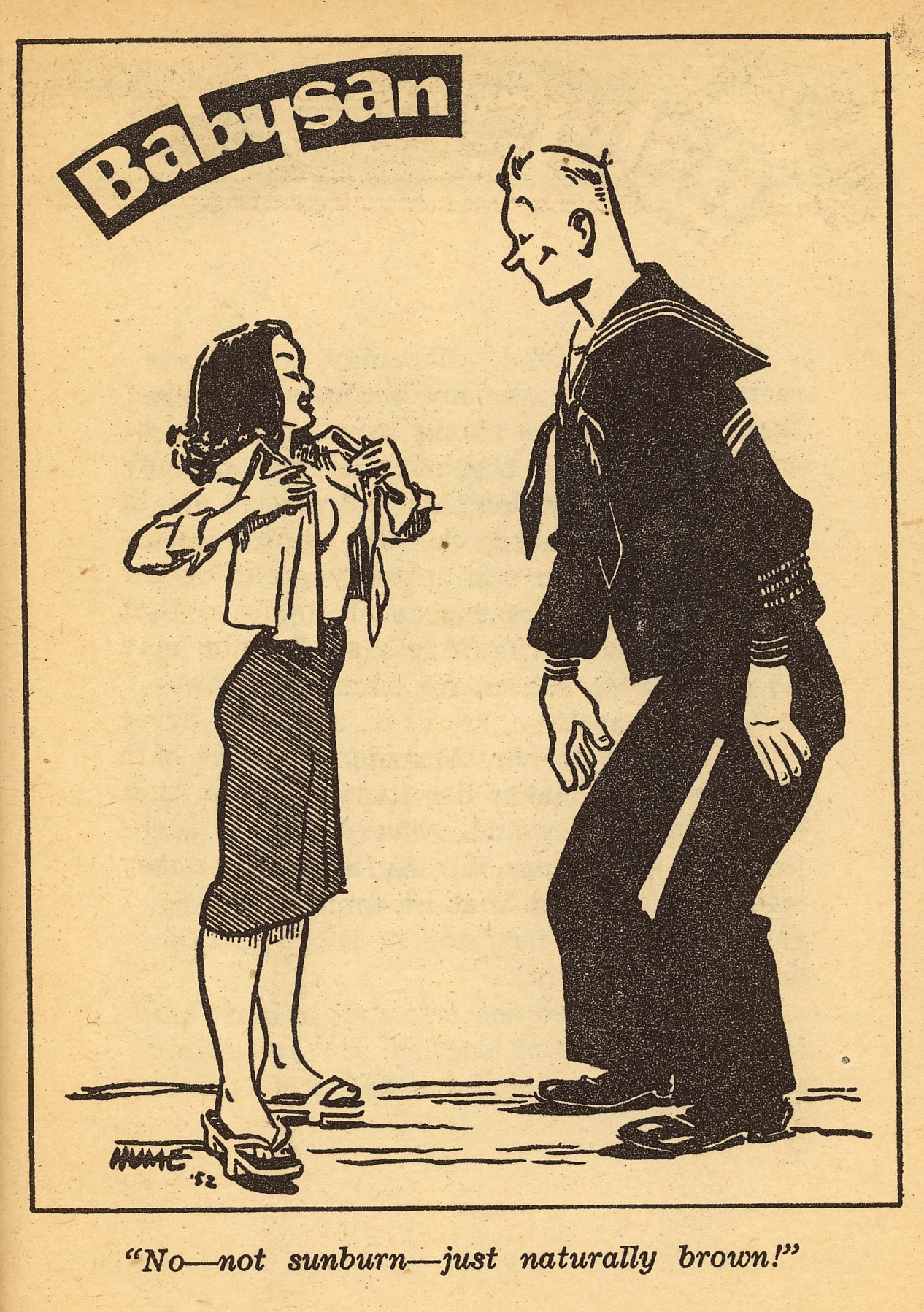

The question of what is missing from a document or source can be just as productive to ask as the question of what it contains. In Babysan there are a number of telling absences or ellipses. Perhaps most glaringly, the social world of Babysan is radically simplified and homogenous, suppressing much of the diversity that actually existed both on and off the military base. Social difference in Hume’s telling centers on the opposition between young Japanese women and their American boyfriends. That difference is gendered, and cultural, and it is also clearly racial, as underscored by the several cartoons that turn on the question of skin color. “No—not sunburn—just naturally brown!” is the caption to one, in which Babysan blithely opens her blouse for an ogling sailor [Babysan, 84-85; see also 37].[6] [figure 4]

Fig. 4

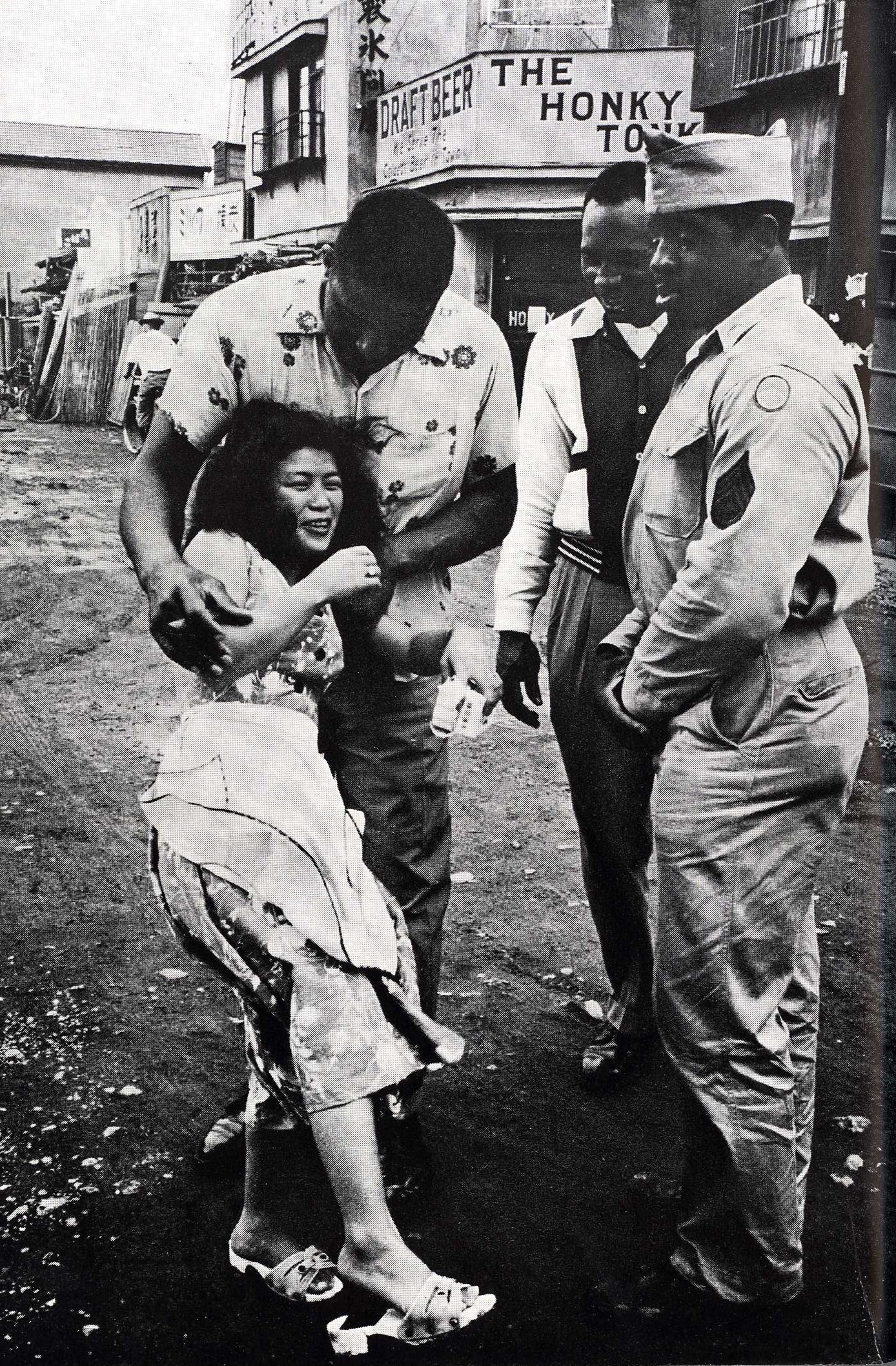

Yet Babysan’s focus on the fascination of white soldiers with the “colorful” bodies of Japanese women obscures the fact that not all Allied troops were white. A significant minority of African-Americans served in the Occupation, where they were segregated in all-black units until as late as 1951, and endured discriminatory policies and treatment on duty as well as off. Also important in occupied Japan were Asian-American and especially Japanese-American personnel, both male and female. Similarly, among the British Commonwealth troops who occupied Japan were Indian, Nepalese, and Maori units. Although there is ample evidence of social interaction, including sexual relations, between Japanese and non-white soldiers, Babysan’s occupiers are exclusively white men.[7] To include representations of non-white sailors was perhaps to introduce divisive questions of internal difference and inequality that would have mitigated against the humorous, “morale-building” function of military entertainment such as Hume’s cartoons. [figure 5]

Fig. 5. 1957 photograph by Tokiwa Toyoko of African-American servicemen and a Japanese woman, in Yokohama [8]

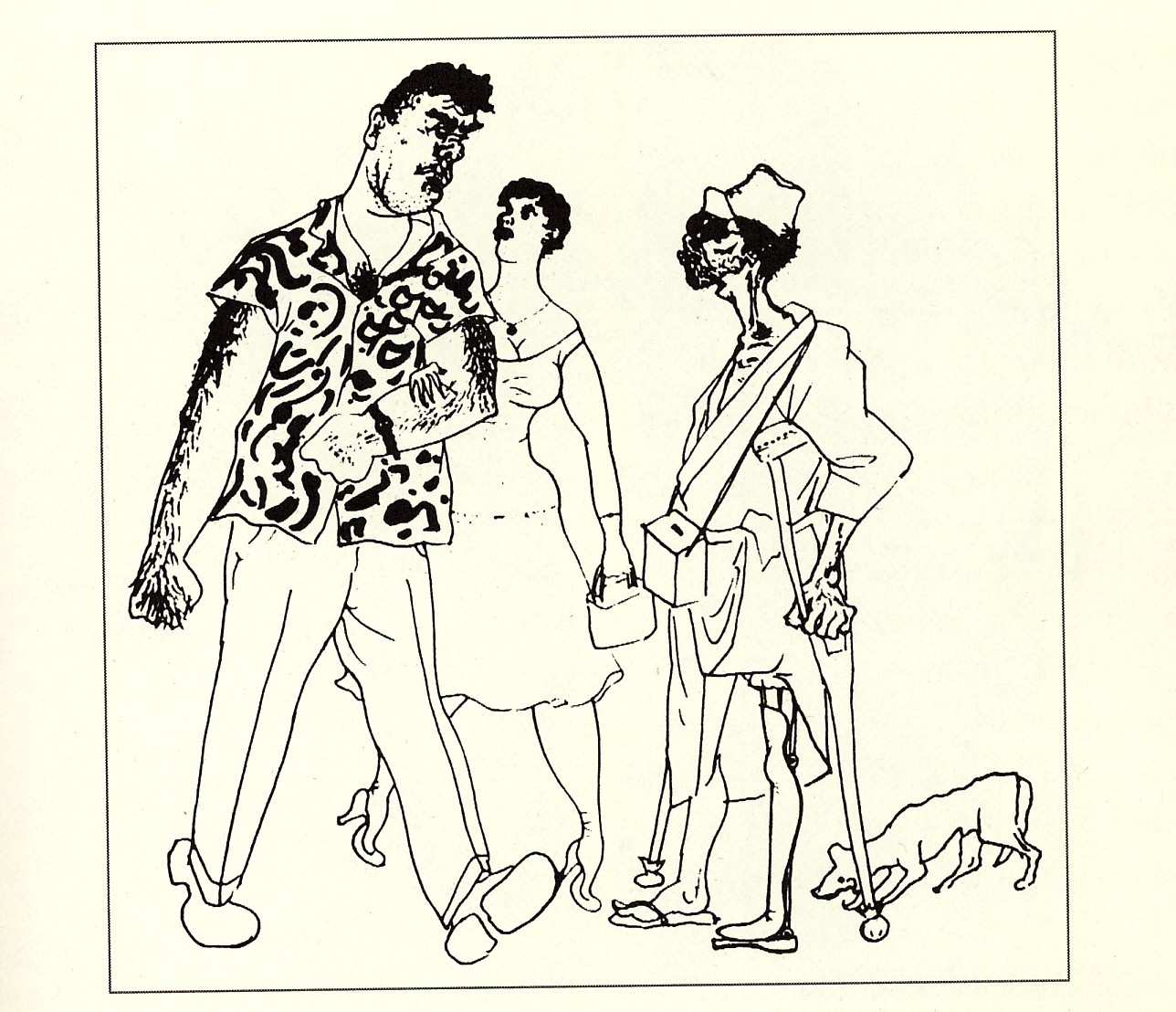

It may have been a similar logic that dictated the omission of any reference to Japanese society beyond the young women who “butterflyed” about military installations. Representations of anyone else might have reminded the viewer of other segments of the native population who were less complaisant, or who even resented the presence of Allied troops. [figure 6]

Fig. 6. Image taken from John W. Dower, Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II, 135. In this early postwar cartoon by Endô Takeo, the disabled Japanese veteran contemplates his former enemy, an American soldier who is enjoying the spoils of victory in occupied Japan.

During the Occupation and after, military bases, the neighborhoods of bars and brothels that grew up around them, and the denizens of both were regarded with suspicion, distaste, and anger by much of Japanese society. In addition to representing all the ignominy of foreign military occupation, to many Japanese the bases seemed almost inevitably to pollute the areas around them with a noxious mixture of alcohol and drugs, prostitution, violence, gambling, and black-marketeering. Indeed, since the 1950s there has been ongoing social activism by Japanese groups who protest U.S. military bases, and the various ways in which they can be said to harm surrounding communities.

Another important omission from Babysan is the much broader spectrum of interactions that occupying troops actually had with local women. It is not surprising that Hume would choose to overlook the ubiquity of ordinary prostitution, for example, or the regular occurrence of rape and other forms of sexual violence.[9] Neither was consonant with either the public image or the self-image of the U.S. military. What may be a little more difficult to understand, however, is Babysan’s silence on the possibility of lasting relationships leading to marriage. Instead, the basic assumption running throughout the collection is that: “All good things must come to an end. The boyfriend’s association with Babysan is no exception” [Babysan, 120]. In fact, however, many of the “associations” between Japanese women and their soldier boyfriends did not end; beginning as early as 1947, ever-increasing numbers of couples chose to marry. By the end of 1952, according to one source, over 10,000 Americans had married Japanese women. That number would only grow over the decade. Estimates of the numbers of Japanese “war brides” who migrated to the U.S. with American fiancés or husbands during the 1950s and 1960s have ranged as high as 50,000. To this must be added the figures for those who married Allied soldiers but stayed in Japan, and also those who migrated to other countries, such as England and Australia.[10]

In ignoring the very real and growing phenomenon of marriage between U.S. servicemen and Japanese women, Babysan points instead to the deep discomfort that surrounded the topic in the early 1950s. As noted above, the official military policy in Japan was to discourage “fraternization,” although in practice it tended to be tolerated as a necessary evil. Until U.S. immigration law was changed in 1952, however, marriage between Americans and Japanese nationals was explicitly and formally banned, on the grounds that Japanese were legally unable to enter the U.S. According to the so-called Oriental Exclusion Act (1924), Japanese (along with Chinese, Indians, Filipinos, and other “Orientals”) could not be admitted to the U.S. because their race made them ineligible for citizenship. And even after the passage of the McCarran Walter Act of 1952, which created limited opportunities for Asian immigration, “anti-miscegenation” laws criminalizing marriage (and sometimes even sexual relations) between members of different races remained in force until the 1960s in many individual American states. Hume’s insistence on the impermanent nature of relationships between American sailors and their Japanese girlfriends reflected not reality, therefore, but the desired effect of federal, state, and military laws, and the tense race relations that underpinned them.[11]

III. Babysan Travels

Babysan also serves as indirect evidence of the profound and enduring impact of the Occupation outside Japan. The tens of thousands of Japanese war brides who migrated to the U.S. and other Allied countries during the late 1940s and 1950s, for example, represented an important demographic event in the U.S. and elsewhere. Indeed, during the approximately forty years between the Oriental Exclusion Act of 1924 and the 1965 Immigration Act, when the migration of Asians to the U.S. was radically curtailed, Japanese (and Korean) war brides were practically the only Asians to enter the country in significant numbers. Furthermore, the fact that the majority of these Asian migrants were married to white men (although sizable minorities married Asian-Americans and African-Americans), and became mothers to mixed-race American children, represented a notable challenge to the segregationist Jim Crow laws and ideology of 1950s America. The process by which mainstream American society came to accept Japanese and other Asian war brides might be said to have begun with cartoons like Babysan, and continued with other artifacts of American popular culture, such as popular songs, best-selling novels, and big-budget Hollywood films.[12] As one scholar has suggested, the extensive and increasingly positive coverage in the U.S. mass media of Japanese war brides and their “mixed” marriages with white men served in part to stand in for, and also occlude, larger and more intractable problems of black-white race relations in the dawning Civil Rights era.[13] [figure 7]

Fig. 7. Poster for Sayonara (dir. Joshua Logan, 1957)

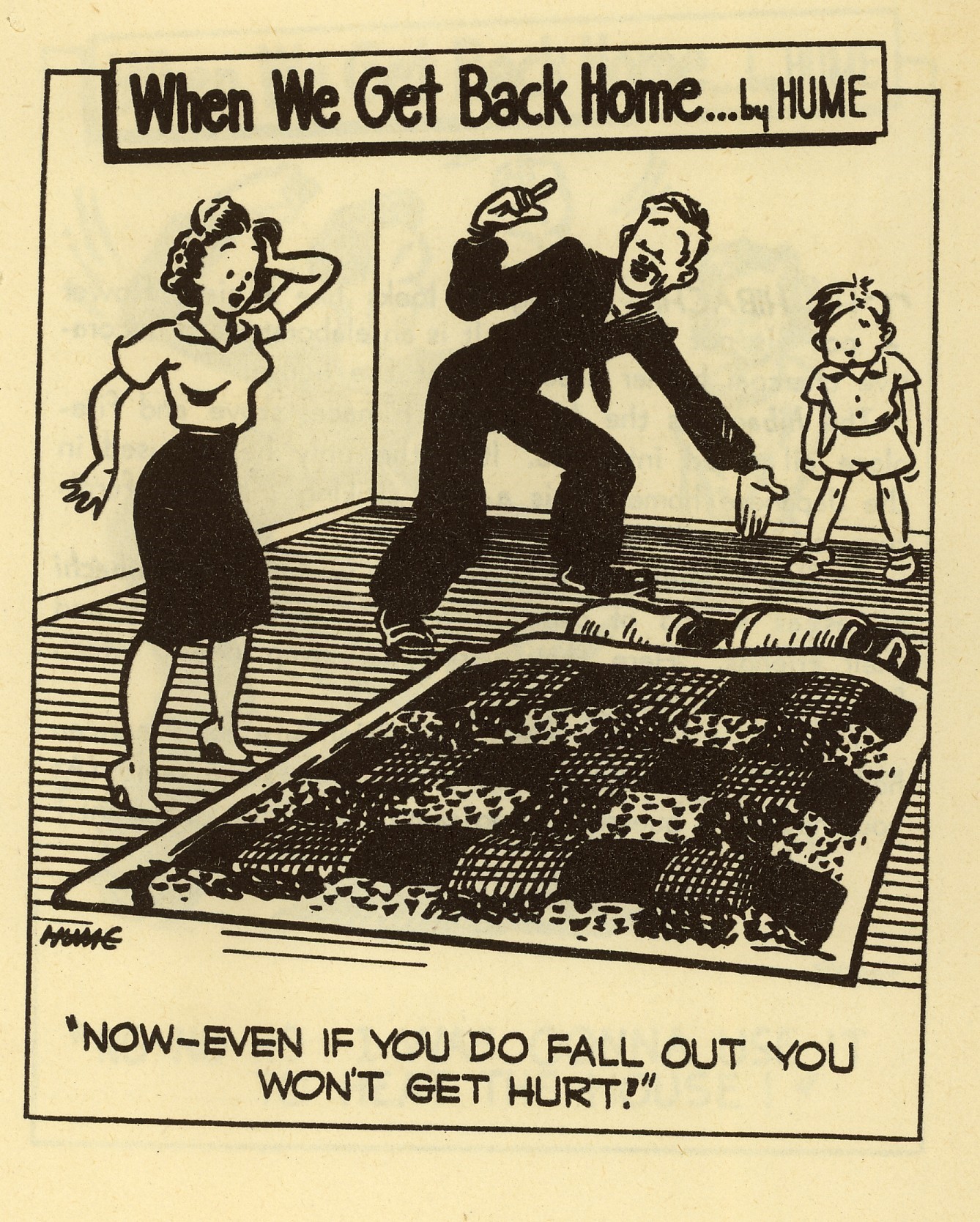

As noted above, Babysan also suggests the possibility of an unintended Japanization of Americans that accompanied the effort to Americanize Japanese. In another volume of cartoons also published by Hume in 1953, titled When We Get Back Home from Japan, the repeated joke is that sailors shipped back “stateside” have retained some of the customs and tastes they picked up in Japan. American women look on in bemusement as their husbands sit on the floor, pick up telephones uttering the phrase “moshi moshi,” and try to open doors as if they were sliding shoji [When We Get Back Home from Japan, 5, 113, 24-25]. It is true, however, that the 1950s witnessed the rising popularity in the U.S. of Japan-themed culture—ranging from films, books, cuisine, and fashion to architecture and home design. The reasons for the growing 1950s American interest in Japanese art and design, including elements of interior décor such as shoji, are complex, but the Occupation experience was surely one important factor.[14] [figure 8]

Fig. 8

Finally, there is another sense in which Babysan might be said to “travel”--and also to persist. Hume’s cartoons are a vivid record of many of the habits and customs, attitudes, and images that were generated at the intersection of a war-torn East Asian society and expansive U.S. military installations. While the Occupation of Japan ended formally in 1952, hundreds of thousands of young American soldiers continued to cycle in and out of large, permanent U.S. military bases in Japan through the 1950s and beyond. U.S. bases in Japan were intimately connected, moreover, to American military involvement in other parts of Asia. In the Korean War, for example, U.S. bases in Japan served as the main staging area and sanctuary for American forces fighting on the peninsula. A decade later, the U.S. fought the Vietnam War from bases and installations in the Philippines, South Korea, Taiwan, Guam, Okinawa, and also, again, Japan.[15] To give just one example of the way Babysan “traveled,” the very term “babysan,” like many other words, phrases, and images that first gained currency in occupied Japan, continued to be in use by American troops during the Vietnam War. According to one dictionary of Vietnam war slang, “babysan” was “used frequently in Vietnam,” where it referred to “an East Asian child; a young woman.”[16] Thus elements of “Babysan” culture have lived on and circulated within the massive U.S. Pacific Command--the sprawling complex of hundreds of military installations in the Pacific region that project American power in Asia and, more recently, toward the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean. Many of those installations, especially in Okinawa and South Korea, are even today surrounded by bar neighborhoods centered on the sexual labor of young Asian women.[17]

In conclusion, this essay has sought to suggest just a few of the ways in which it is possible to read a single documentary source for insights into the Allied Occupation of Japan—and into the postwar history of Japan, the U.S., and East Asia. By considering one cartoonist’s humorous representations of interactions between American soldiers and Japanese women, we can deepen our understanding of a crucial event in twentieth-century world history, and its ongoing relevance for the present.

[1] I take these numbers on occupying troops in Japan from Eiji Takamae, Inside GHQ: The Allied Occupation of Japan and its Legacy (New York: Continuum, 2002), 53-55, 125-135.

[2] Information on the U.S. military presence in present-day Japan can be found on the official website of USFJ (U.S. Forces, Japan): http://www.usfj.mil.

[3] Bill Hume, with John Annarino, Babysan: A Private Look at the Japanese Occupation (Tokyo: Kasuga Boeki K.K., 1953).

[4] On prostitution as well as onrii, see: John Dower, Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II (New York: W. W. Norton and Co., 1999), Chapter 4; Takemae, 68-71; Sarah Kovner, Occupying Power: Sex Workers and Servicemen in Postwar Japan (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2012).

[5] On popular music in Japan during the Occupation years, see Michael K. Bourdaghs, Sayonara Amerika, Sayonara Nippon: A Geopolitical Prehistory of J-Pop (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012), Chapter 1. Many of the original recordings, as well as later versions, can be found on Youtube. See, for example, Harry Belafonte’s several recordings of his hit “Gomen-nasai.”

[6] According to the racial classifications that prevailed in 1950s America and elsewhere, the skin color of Japanese and other Asians was yellow. While Babysan emphasizes the idea that Japanese women are “colored,” Hume avoids describing Japanese skin color as yellow, and refers instead to its “brownness.”

[7] On ethnic (and gender) diversity among Allied troops in occupied Japan, see Takemae, 126-137.

[8] Tokiwa Toyoko, Kiken na adabana (Tokyo: Mikasa shobô, 1957), 43.

[9] On sexual violence perpetrated by Allied troops in Japan, see Takemae, 67; Kovner, 49-56.

[10] The figure of 10,517 marriages by 1953 is cited in Anselm L. Strauss, “Strain and Harmony in American-Japanese War-Bride Marriages,” Marriage and Family Living 16:2 (May 1954), 99-106. On the numbers of Japanese women who migrated to the U.S. as war brides, see: Bok-Lim C. Kim, “Asian Wives of U.S. Servicemen: Women in Shadows,” Amerasia 4:1 (1977) 91-115; Rogelio Saenz, Sean-Shong Hwang, Benigno E. Aguirre, “In Search of Asian War Brides,” Demography 31:3 (August 1994), 549-559.

[11] On the ban on marriages between Americans and Japanese, see Yukiko Koshiro, Trans-Pacific Racisms and the U.S. Occupation of Japan (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), 156-200. See also: Susan Zeiger, Entangling Alliances: Foreign War Brides and American Soldiers in the Twentieth Century (New York: New York University Press, 2010), 181-189.

[12] See, for example, the 1957 Hollywood film Sayonara, starring Marlon Brando as the American military officer who marries his true love, a Japanese woman.

[13] Caroline Chung Simpson, An Absent Presence: Japanese Americans in Postwar American Culture, 1945-1960 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2001), Chapter 5.

[14] For further discussion of the “Japan Boom” in 1950s America, see Brandt, Japan’s Cultural Miracle: Rethinking the Rise of a World Power, 1945-1965 (forthcoming, Columbia University Press).

[15] For a discussion of Japan’s involvement in the Vietnam War, see Thomas R. H. Havens, Fire Across the Sea: The Vietnam War and Japan, 1965-1975 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987.

[16] Tom Dalzell, Vietnam War Slang: A Dictionary on Historical Principles, (New York: Routledge, 2014), 5

[17] A good introduction to this topic is provided in Saundra Pollock Sturdevant and Brenda Stoltzfus, Let the Good Times Roll: Prostitution and the U.S. Military in Asia (New York: The New Press, 1992).