The ABCs of the U.S.-Japan Relationship: Alliance, Business, and Culture

The ABCs of the U.S.-Japan Relationship: Alliance, Business, and Culture

A famous Japanese book of the 1200s begins, “Ceaselessly the river flows, and yet the water is never the same.” Eight hundred years later, our world is changing ever more swiftly, and the concerns of today may bear little resemblance to our worries of yesterday. Through all that, some things have a constancy that belies the turbulence on the surface. For over 150 years, the relationship between Japan and the United States has been one of those constants, changing with the times, yet with an underlying resiliency that surprises observers. Even as both countries deepen their relationships with other nations, each will remain of key importance to the other, not least because of a host of common values and visions for the future.

For the past several decades, Americans and Japanese have found their views on the world and key questions about policy moving closer together. Shared visions of individual freedom, democratic institutions, entrepreneurship, and cultural expressions have helped forge an alliance of interests at both the private and public level. At the same time, naturally, serious reservations about U.S. foreign policy remain in Japan, while Americans wonder if they shouldn’t continue to move closer to a rising China. The result is a complex and interdependent relationship in which familiarity breeds both solidarity as well as contempt. In this essay, I give the simple ABC’s of the U.S.-Japan relationship: Alliance, Business, and Culture. These, broadly drawn, will illustrate the evolving nature of the bridge across the Pacific.

Alliance

The alliance between Japan and the United States will be 50 years old in 2010, marking one of the most successful bilateral relationships in modern history, and one that has played a key role in maintaining stability and promoting development in East Asia. Today, the alliance faces challenges from a rising China, increased interdependence in Asia, and threats from North Korea. Japan’s need for energy resources and trade markets also pose a potential point of friction between Washington and Tokyo. Yet underlying all those potential problems is the shared value system that guides both Japanese and American foreign policy. Each, working together as well as separately, is committed to supporting liberal political and social systems and helping freedom take root in Asia.

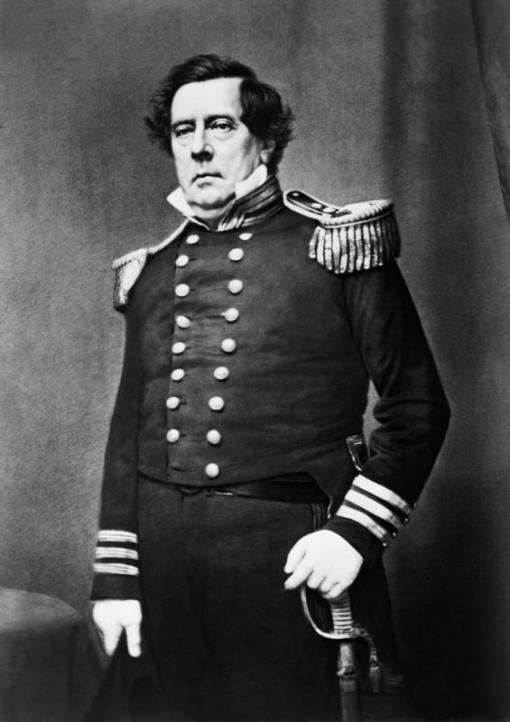

Such was not always the case, of course, especially in the first century of the U.S.-Japan relationship. The two countries first encountered each other during the 19th century, when the young American nation sent its whaling and naval ships to the western Pacific Ocean. During this era of imperialism, Japan was facing increasing pressure from European nations to open up its shores after 200 years of near isolation. When U.S. Commodore Matthew C. Perry arrived in Japan in 1853 demanding that Japan sign commercial treaties with America, many younger Japanese samurai realized that their old system would have to change. Within 15 years, a new government had risen in Japan, overthrowing nearly 700 years of samurai rule, and committed to opening the country up to the knowledge of the modern world. This government, named after the ruling Meiji Emperor, expanded Japan’s relations with many countries, but especially with America, whom it saw as a young nation like itself taking over from the older civilizations that surrounded it.

Portrait of Commodore Matthew C. Perry

Donated by Corbis-Bettmann

For the rest of the 19th century, the American Republic rebuilt itself after the devastation of the Civil War and spread its control over the continent to the Pacific Ocean. Japan embraced policies that modernized its economic and social systems, and consistently used its diplomacy to try and overturn the stigma of the “unequal treaties” imposed back in the 1850s. Yet at the very end of the century, both embraced new policies of expansion that not only copied European models of colonialism, but would soon set them set them on a collision course.

In 1894, Japan launched a war against Qing China for control over the Korean peninsula; in winning, it gained control of Formosa (Taiwan), yet found itself opposed by Tsarist Russia in Korea. Ten years later, Tokyo attacked Russian forces in the Far East, ultimately winning a bloody war that gave it sole control over Korea, and a preponderant position in northern China. At almost the same time, in 1898, the United States attacked Spanish forces in the Philippines as part of a larger war over Cuba. President William McKinley then annexed and colonized the Philippines, thus making the United States a Pacific power. Both Tokyo and Washington suddenly found themselves as imperial powers, replacing the traditional great states in the Asia Pacific region. More importantly, each began to view the other as the largest potential threat to their ultimate goals of maintaining superiority in Asia.

This era of colonialist tension grew from the 1910s through 1930s. As Washington looked with growing unease on Tokyo’s desire for a growing sphere of influence in East Asia, Japanese strategists felt that the U.S. and European powers were explicitly aiming to limit Tokyo’s naval buildup. Once Japan’s Kwangtung Army took control of Manchuria in 1933, and then spread into mainland China in 1937, the United States slapped economic sanctions on Tokyo. Repeated negotiations left the two sides in deadlock, and the Japanese cabinet decided to strike while conditions remained in their favor, in December 1941. The four devastating years of war between Japan and the United States ruptured Japan’s pretensions at becoming the hegemon of Asia, yet they ultimately offered Japanese leaders a different path to international power, thus ushering in the third political wave between America and Japan.

The U.S. Occupation of Japan blended into Washington’s global Cold War struggle against Communism. Convinced of the need to have a solid partner in the Pacific to anchor the American presence, Presidents Truman and Eisenhower forged a mutual security treaty with Tokyo that guaranteed protection of Japan while also subordinating Japanese national security policy to alliance objectives. Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida accepted the bargain as a way to rebuild Japan’s shattered economy and society. Although contentious in its early years, the alliance became widely accepted in Japan as the best political arrangement in an uncertain and changing region. For forty years during the Cold War, Tokyo worked with Washington to provide a credible political and security alternative to Chinese and Russian Communism in Asia.

Signing of US-Japan Security Treaty 1951

Donated by Corbis-Bettmann

Politically, the umbrella of the alliance worked both to limit Japan’s freedom of action but also to promote its new national interests of economic growth. Tokyo became an active participant in global multilateral organizations, particularly the U.N., and it still participates regularly, usually voting similarly to the United States. At the same time, the alliance provided reassurance to nations in Southeast Asia harboring bitter memories of World War II when Japan began to reach out in the 1970s, offering development aid, technical assistance, and trade. Throughout the 1990s, Japan was the number one provider of foreign aid, focusing on infrastructure development in Asia and Africa, as well as health and sanitation initiatives.

Since the end of the Cold War, Tokyo has increasingly identified itself with the support of liberal democratic systems in Asia and around the globe. That led to a particularly close relationship between Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi and U.S. President George W. Bush, with Japan sending Self-Defense Forces to Iraq, Afghanistan, and the Indian Ocean in support of the U.S. war on global terrorism, despite domestic opposition and criticism. Yet constitutional restrictions on Japan’s ability to engage in collective self defense continues to limit the level of direct U.S.-Japan security cooperation. Policymakers in Washington and Tokyo have worked for over a decade to modernize the alliance to better reflect its mission of maintaining stability in East Asia as well as providing for the defense of Japan.

At the same time, of course, Japanese from policymakers to grass-roots groups have been wary of being entangled in American foreign policy to the detriment of their own country. Strong voices were raised against Koizumi’s dispatch of SDF troops to the Middle East, and others, such as Democratic Party of Japan head Ichiro Ozawa, claim that Japan must work more closely with the United Nations, and not in un-constitutional methods with Washington. There is a strong movement supporting closer Japanese identification with Asia, including China, as well. The political relationship between Japan and the United States continues to serve as the core of both countries’ Asian policies, but also continually navigates with these other voices and works with nations across the Asia Pacific region.

Business

A second pillar of the U.S.-Japan relationship is the business and economic ties between the two. As the two largest economies in the world, Japan and America play a unique role in global finance, production, and trade. Over the past decades the two economies have become increasingly intertwined, and changes in either one have nearly immediate repercussions in the other. In addition to their bilateral dependence, both Japan and the United States have an interest in furthering liberal trade regimes, strengthening free trade, and establishing global economic standards.

It is often forgotten that business interests first drew Japan and America together. The first American ships to visit Japan were whaling vessels in search of ports of call and supply stations, yet soon the U.S. Navy looked to Japan as a source of coal for its new steamers. These converging U.S. interests led to the expedition of Commodore Perry in 1853-54 and the dispatch of Townsend Harris as first U.S. consul in 1856. Harris’ 1858 Treaty of Amity and Commerce marked the beginning of the U.S.-Japan economic relationship, but also helped destabilize the 200-year old Tokugawa shogunate. It was the reaction of the samurai reformers in Meiji that catapulted economic reform to the top of their domestic agenda.

Over the next decades, Japanese government and business worked together to create export industries, such as textiles and tea. By the turn of the century, Japan was starting to become a major industrial producer, although largely oriented towards further capital development. Japan’s endemic lack of natural resources was from the beginning a long-term constraint on the country’s economic growth, and it led directly to Japan’s disastrous decisions to begin expanding throughout Asia. Colonization of Taiwan, influence over the Korean peninsula, and control over Manchuria became the objectives of Japanese foreign policy, but each was seen as a vital component of Japan’s economic development, either for raw materials, foodstuffs, or markets. Tokyo’s relentless expansion, driven in large part by the Imperial Army, led directly to the clash with the United States over hegemony in Asia.

It was the need to rebuild its industrial base after defeat in World War II that pushed Japan firmly on the path of export industries. In the early postwar period, Japan produced largely low value goods, such as textiles and toys; by the 1960s, it was moving up the consumer value chain, exporting electronics by Sony and automobiles by Toyota and Honda. Japan became the world’s largest shipbuilding market, and with government support, the country took full advantage of the semi-conductor revolution in the 1970s, becoming a major producer of high-end electronic goods. The United States became Japan’s largest trading partner in the postwar period, a position it only recently surrendered to China. As Japan’s economic growth took off in the 1980s, it began in investing in the United States; while most of the spectacular purchases of those days have been sold off, Tokyo remains the largest purchaser of U.S. Treasury bonds, implicitly helping to support America’s debt.

Today, Japan and the United States are challenged by their transition to a post-industrial economic posture, the current global economic collapse, and the economic rise of China. Closer coordination on free trade between the two has been hampered by resistance in Japan to opening up its agricultural market, while the U.S. has resorted to targeted market access demands since the 1980s, particularly in autos, glass, film, and agriculture. Economic tensions between the two came to a head during the 1990s, due largely to the enormous current accounts surplus Japan held against the United States. Recently, Washington has faced some of the same economic problems with China, yet has moved more swiftly than it did in the 1980s to institute high-level political mechanisms, such as the Strategic Economic Dialogue, to address issues with Beijing. Both Japan and the United States, moreover, find their economies increasingly dependent on cheaper Chinese goods and Chinese investment (for America).

Americans and Japanese face particularly daunting economic challenges in the coming decades, and divisions over free trade will continue to dog their relations, especially in international negotiations. Common ground on intellectual property rights, labor conditions, and consumer product safety, on the other hand, will bind both partners together in global trade agreements. In addition, both remain leaders in global research and development, and continue to have the highest quality consumer brands with worldwide appeal. And, as the 2008 financial crisis showed, American institutions have much to learn from Japan’s difficulty in restructuring and creating transparency during the 1990s and early 2000s. (Click here for resources related to the global economic crisis and Japan.)

Culture

Foreign relations between most counties is largely a matter of diplomacy and trade, and indeed managing those issues has taken up the majority of effort in the U.S.-Japan relationship. Yet as much as trade negotiations and security agreements have preoccupied officials in both countries, Americans and Japanese have been tied together by a deep and enduring fascination with each other’s culture. This cultural leg of their relationship has in many ways been as durable as the political and economic legs discussed above. Moreover, it is almost unique among America’s bilateral relationships, and equaled only by that with Great Britain or France.

Decades before Americans and Japanese had trade relations or any sustained personal contact, the two countries were becoming fascinated with each other through second-hand tales and occasional exchange of luxuries. Once trade treaties were signed in the 1850s and the Meiji government deepened relations with the West, numerous Japanese and Americans traveled across the Pacific—the Japanese to learn, the Americans largely to see. Accounts of Japan became best sellers in America, while Japanese looked to the United States as a source of economic wisdom and modernized ways of living. Within a few decades of the beginning of formal relations, exchange societies began forming in both countries. The most prominent in Japan was the America-Japan Society of Tokyo, founded in 1917, while among the plethora of organizations in the United States, the Japan Society of New York took pride of place after its 1907 debut.

Through these organizations, and later through Japanese studies programs at major universities, Americans were exposed to Japan’s traditional arts, from pottery to flower arrangement. Student exchanges began in earnest in the 1930s, and the Society for the Promotion of International Culture served as Tokyo’s public diplomacy arm before and after World War II. After the war, private organizations, such as the International House of Japan, also served to rebuild ties shattered by conflict. American educators and intellectuals made speaking tours throughout Japan, while the revived Japan Society in New York spearheaded a new era of cultural exchange in the United States.

Over the decades, the nature of U.S.-Japan cultural exchange has shifted away from more traditional forms towards youth-oriented popular culture. Perhaps a harbinger of the shift appeared when American moviegoers became fascinated with Akira Kurosawa or the Japanese New Wave films and sports aficionados flocked to martial arts, but by the 1980s, consumer-oriented promotion of Japanese anime and manga had begun to overshadow the traditional arts. American universities began adding classes in Japanese sports and pop culture, even as interest in Japan’s economic history and social experience began to waver. Over in Japan, teenagers became hooked on American hip-hop music and fashions, while American-style fast food chains spread throughout Japanese cities, lending many to equate American culture with consumer goods. It will be interesting to see how Japan’s shift toward an aging society changes its popular culture and its relations with America, as well as how both countries define traditional lifestyles of the elderly in coming decades. At the same time, countries throughout Asia are increasingly patterning their own popular culture on Japan’s highly exportable models, thus reducing the uniqueness of the U.S.-Japan cultural tie.

Regardless of whether one celebrates or deplores current trends, fashions in U.S.-Japanese cultural exchange have come and gone. What remains unchanging is the apparently enduring interest each society retains in the other. Both Americans and Japanese respect and have interest in cultures around the globe, of course, yet their trans-Pacific ties still remain of a different order, and have increasingly come to influence the daily lives of millions on both sides of the ocean. From interior design to clothing styles, from gardening to food, Americans and Japanese have engaged in a decades-long exchange that has helped each change. This grass-roots exchange is strengthened by the shared political visions and economic interdependence of the two countries, which benefit their own economies and societies as well as those in Asia and beyond. U.S.-Japan relations will remain complex, often frustrating, and yet undeniably close in the coming decades, just as they have for over a century and a half.